Ming Dynasty Tombs

The resting place of 13 Ming emperors, representing over 230 years of imperial history.

Surrounded by mountains and rivers, forming the ideal Feng Shui “land of eternal peace.”

The Sacred Spirit Way, lined with 36 vivid stone statues, guards the emperors for six centuries.

Home to grand architectural masterpieces like Ling’en Hall and the underground palaces.

Rich in cultural treasures, from gold crowns to intricate dragon carvings.

A living history museum where visitors walk through 600 years of royal legacy and craftsmanship.

Friends, beneath our very feet lies a 230-year chapter of Ming dynasty history now slumbering in the earth – welcome to the Ming Tombs Scenic Area! This is not merely a solemn imperial burial ground, but an open-page living history book. Every brick and stone bears the wisdom of feng shui, while each palace conceals architectural legends. We shall now proceed along the blue-stone path of the Sacred Way, touching the stone sculptures that have retained their lustre for six centuries, as we uncover the untold secrets within this ‘eternal abode of good fortune’ for China's emperors.

I. First Glimpse of the Thirteen Tombs: An Imperial Garden Encircled by Mountains and Water

First, please look up towards the distance — that undulating mountain range, resembling the spine of a colossal dragon, is known as the Jundu Mountains. Observe how it encircles the entire Thirteen Tombs scenic area, cradling it within its embrace like a natural green barrier that shields against the frigid northern winds; Now observe the winding Dasha River at the mountain's base. Its crystal-clear waters flow gently through the valley, sunlight glinting upon the surface like scattered silver coins. As the ancients observed, ‘Mountains are dragons, waters are veins.’ This landscape of mountains encircling waters embodies the most ideal ‘feng shui treasure land’ cherished in ancient wisdom.

This layout took the emperors of the Ming Dynasty a full two years to discover. Upon ascending the throne, the Yongle Emperor Zhu Di made selecting his imperial burial site his foremost priority. He dispatched three of the most eminent feng shui masters, equipped with their compasses, to traverse the mountains and rivers of North China. First they journeyed to Zunhua in Hebei, but found the mountain slopes too gentle. Next they explored the western outskirts of Beijing, only to discover insufficient water sources. It was only upon reaching this location that the masters, after prolonged compass readings, exclaimed with revelation: ‘Here, with Mount Tianshou as its back, Serpent Hill to its left, Tiger Ravine to its right, and the Great Sands River flowing before it, lies the very dragon's lair described as “fronted by illumination, backed by support, and embraced by flanking sandy hills”!’ Upon hearing this, Zhu Di personally rode out to inspect the site. Standing atop the mountain, he gazed out to see the surrounding peaks like sentinels and the river winding like a jade sash. He immediately declared: ‘This shall be the site of my eternal resting place!’

Subsequently, beginning with the Longling Mausoleum of the Yongle Emperor, thirteen emperors, twenty-three empresses, and over thirty imperial princes and consorts of the Ming Dynasty were successively interred here. Do not underestimate this 120-square-kilometre expanse. It stands not only as China's largest and best-preserved imperial mausoleum complex but also ranks among the world's most extensive surviving imperial burial sites. In 1992, it was honoured as one of Beijing's “World's Greatest Tourist Attractions”!

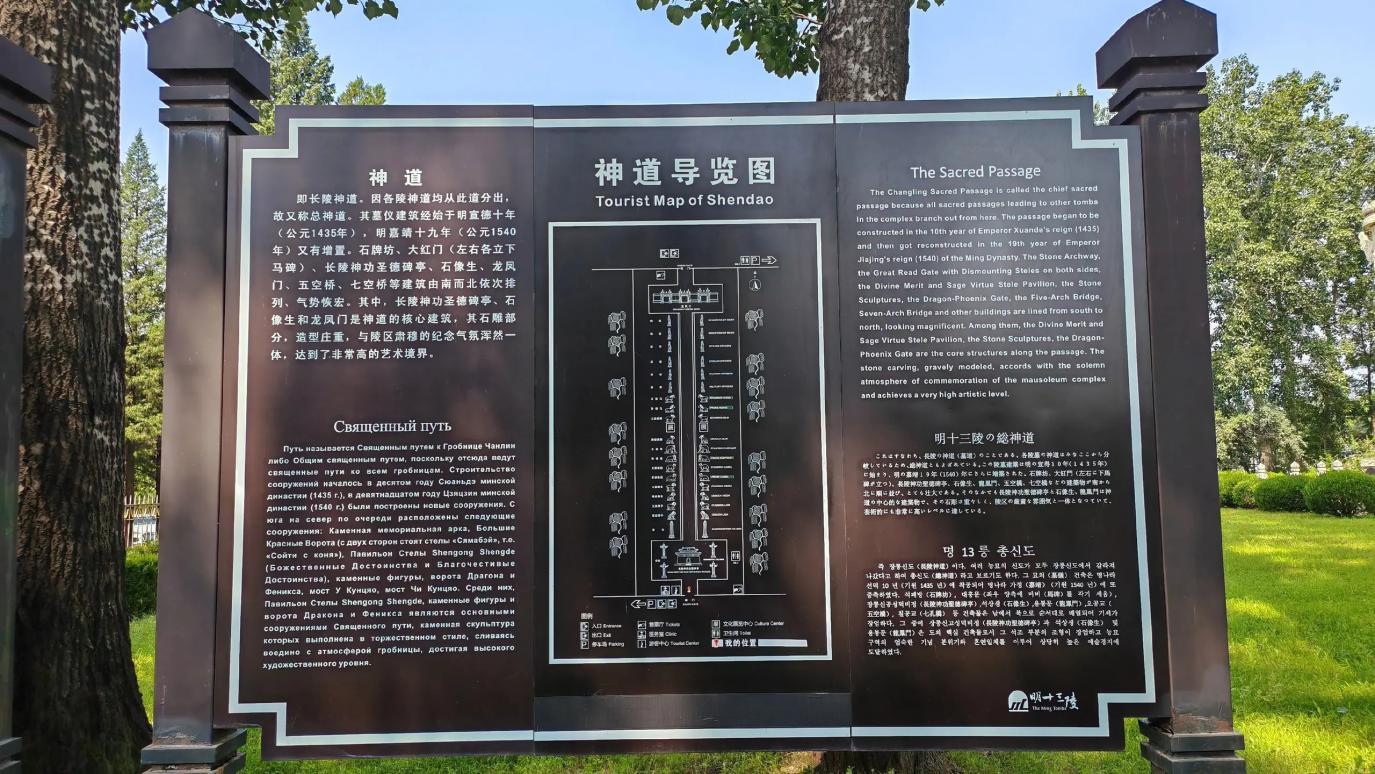

II. The Sacred Path: The 600-Year-Old Stone Guard of Honour

The spot where we now stand is the central axis of the Thirteen Tombs—the Sacred Way. This stone-paved path, stretching some seven kilometres, served as the obligatory route to all imperial mausoleums, much like the imperial avenue before the palace gates, exuding solemnity and majesty. Look ahead: the pairs of lifelike stone sculptures flanking the road are the ‘eternal guardians’ of the emperors, known as ‘stone guardian figures’.

The entire Sacred Way features 36 stone guardians, divided into animal and human categories: 24 animal sculptures—including lions, xiezhi, camels, elephants, qilin, and horses—with each species represented by two pairs, one standing and one kneeling, each displaying distinct postures; Twelve human figures comprise six civil officials and six military generals, each impeccably attired with solemn expressions. Let us first examine the stone elephant — standing 2.6 metres tall and 3.4 metres long, its muscular contours are carved with lifelike precision. Its four legs anchor the ground like pillars, while its trunk curves gently, as if poised to spout water at any moment. Ancient Chinese believed elephants to be ‘gentle in nature yet immensely powerful.’ Placing it here served both to ward off evil spirits and symbolise the stability of imperial rule.

Now observe the stone camel beside it, a rather unusual addition to this stone menagerie. Did you know? Camels hail from deserts and are seldom found in northern imperial tombs. Yet Emperor Yongle specifically ordered this carving, for when he dispatched Zheng He on his voyages to the Western Seas, camels had carried vast supplies for the fleet. This stone camel stands tall and proud, its hump full and rounded, as if still bearing treasures from the Western Regions, silently recounting the splendour of the Ming Dynasty's ‘all nations paying homage’.

Most intriguing is the stone sculpture of the warrior. Observe his pointed helmet, the tassel patterns on which are clearly visible; His armour is layered thickly, the patterns on the plates so finely detailed that every line is discernible. His hands are placed before his chest, concealed within his wide sleeves – this is no sign of the craftsman's laziness, but rather the ancient “bowed hands” salute. During the Ming Dynasty, civil and military officials were required to keep their hands within their sleeves and bow deeply when presenting themselves before the emperor. Even stone sculptures were expected to adhere strictly to this ritual. These stone elephants, erected during the Xuande reign of the Ming Dynasty, have stood here for over 600 years: weathered by torrential rains that allowed wild grass to sprout from their crevices; battered by sandstorms that left mottled marks upon their surfaces. Yet they remain proudly upright, like loyal sentinels guarding the slumbering emperor.

A local legend concerning the stone horses recounts an incident during the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty. A farmer travelling by cart late one night along the Sacred Way suddenly heard the sound of ‘clop-clop’ hooves. Looking up, he saw two stone horses ‘walking’ down from their pedestals, galloping along the stone path with manes fluttering in the wind and emitting distinct whinnies. Terrified, the farmer hid in the grass. When he returned at dawn, the stone horses stood obediently in their original places, though the stone path bore several fresh sets of hoofprints. Though merely a folk tale, it reveals how these stone figures have long ceased to be mere cold stone in the hearts of locals, becoming instead sentient guardians.

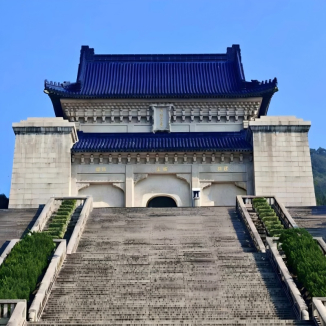

III. Changling: The “Eternal Palace” of the Yongle Emperor

Next, we shall visit the most magnificent of the Thirteen Tombs — the Changling Mausoleum of the Yongle Emperor. When one speaks of Emperor Zhu Di, one might recall his grand achievements: relocating the capital to Beijing, constructing the Forbidden City, and dispatching Zheng He on his voyages to the Western Seas. His Changling Mausoleum, much like his life, exudes a sense of grandeur at every turn.

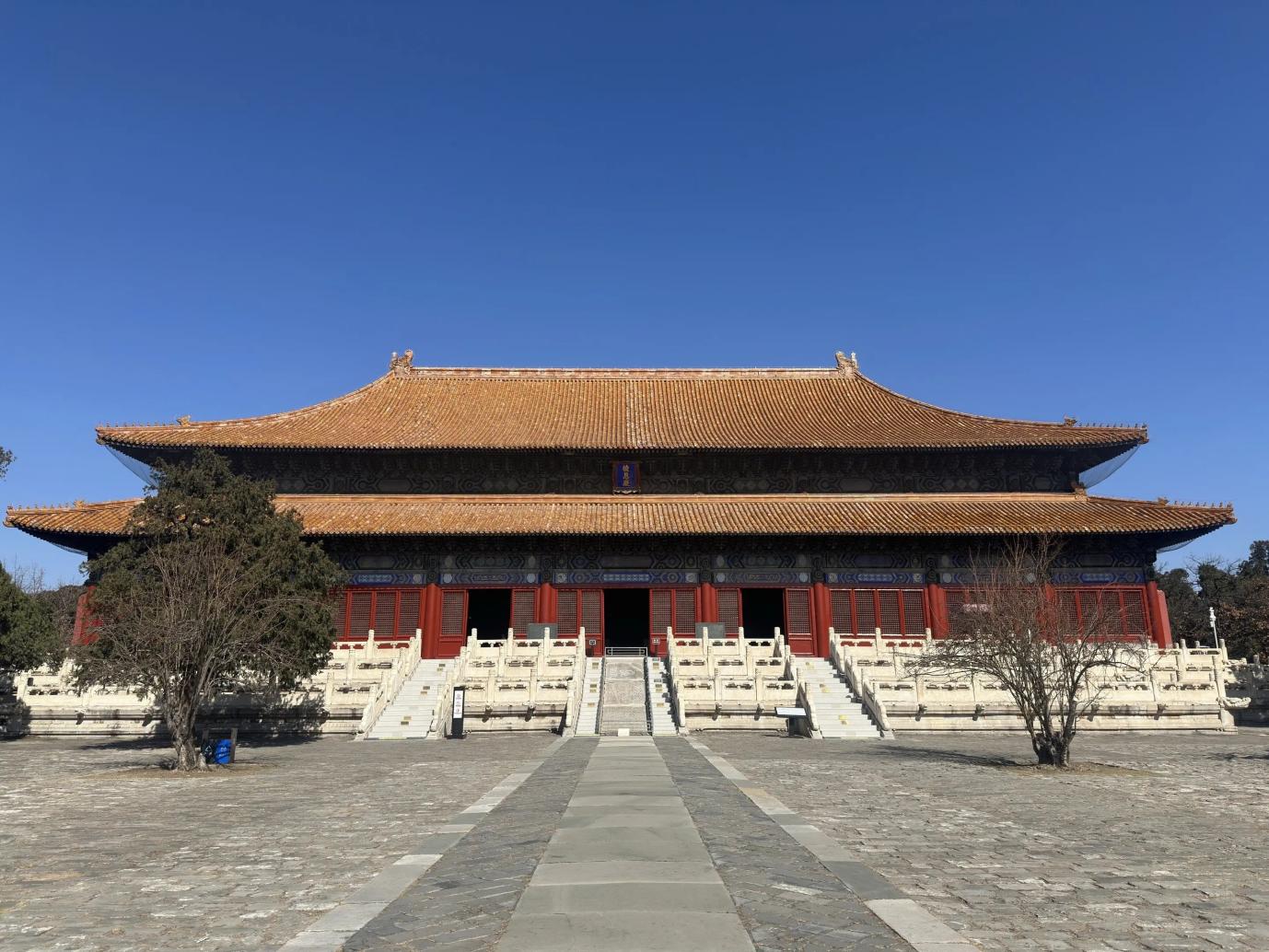

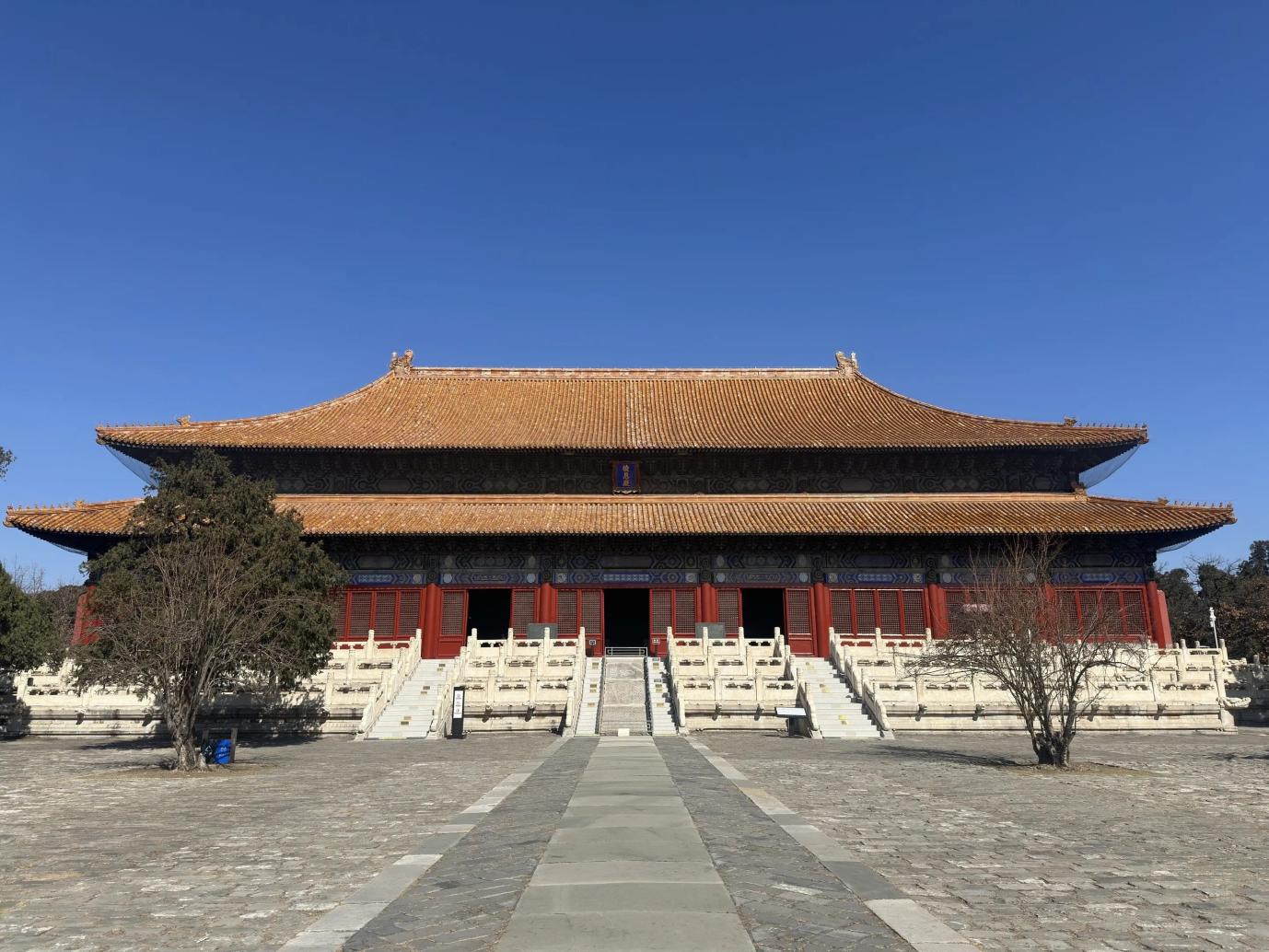

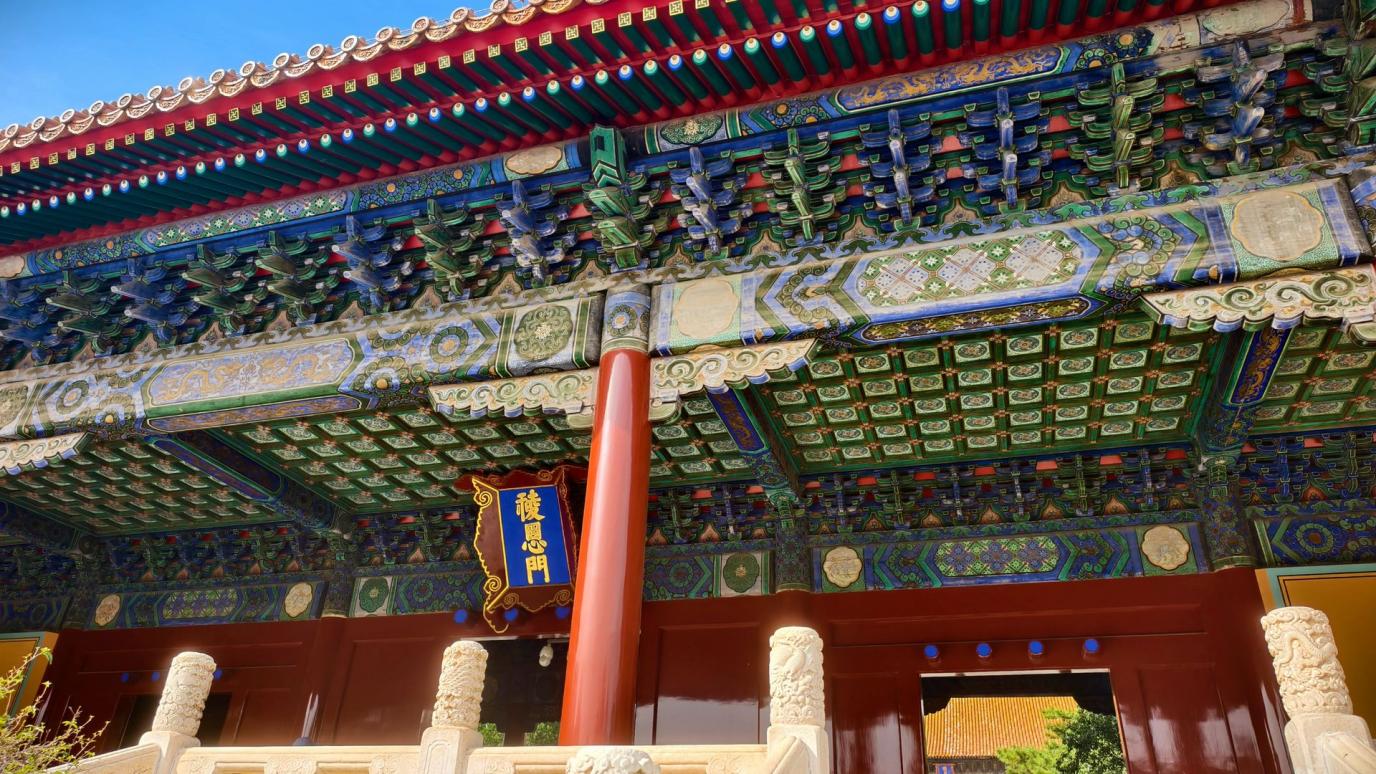

Upon reaching the entrance, visitors are greeted by a towering structure of red brick and yellow tiles—this is the Ling'en Hall, the main ceremonial hall dedicated to honouring Emperor Yongle. Do not underestimate this hall; its scale is second only to the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City, making it one of China's largest surviving wooden structures. Consider its pillars: each stands 14 metres tall with a diameter of 1.17 metres, requiring two adults holding hands to encircle it. More astonishingly, these pillars are carved from single pieces of golden thread nanmu wood!

Golden thread nanmu is a precious timber unique to China, growing in the deep mountains of Sichuan and Yunnan, taking over a century to mature. To harvest these logs, craftsmen had to venture deep into primeval forests, chiselling them out piece by piece with axes before lashing the timber to horses' backs and transporting it over mountains and valleys to this site. It is said that transporting a single nanmu pillar from felling to the Thirteen Tombs took three years, consumed over a thousand labourers, and cost as much as gold – hence the folk saying: ‘One nanmu pillar equals ten years' grain for the common folk.’ Moreover, golden thread nanmu possesses a remarkable quality: it remains rot-proof for millennia while emitting a subtle fragrance that repels insects. As you now enter the main hall, you may still detect the faint, lingering fragrance of nanmu wood in the air—a natural perfume from six centuries ago!

Within the hall, the central position is occupied by the statue of the Yongle Emperor: crowned with a nine-dragon gold diadem, clad in a crimson dragon robe embroidered with five-clawed golden dragons, his left hand resting on his knee, his right grasping a jade sash, his gaze both majestic and serene. Observe the dragon motif on his robe—the five-clawed golden dragon, an emblem reserved exclusively for the emperor. Ministers were permitted only the four-clawed python pattern; to dare use the five-clawed dragon was a crime of treason. Dragon carvings adorn the beams and walls throughout the hall: some dragons surge through seas of clouds, others coil beside jewels. A total of 9,999 dragons, plus the one on the Yongle Emperor's robe, symbolise the ‘Ten Thousand Dragons Paying Homage’ — representing the emperor's supreme authority.

Why did the Yongle Emperor construct such a magnificent mausoleum? In ancient China, imperial tombs were termed ‘underground palaces.’ The Yongle Emperor believed that after death, the soul persisted; he remained emperor beneath the earth and thus required a palace as grand as the Forbidden City to continue ruling his ‘underworld kingdom.’ Moreover, he deliberately situated Changling at the foot of Mount Tianshou's main peak, intending for subsequent emperors to be interred there. This arrangement, symbolising ‘descendants encircling the throne,’ was meant to ensure the Ming dynasty's enduring stability. Regrettably, the Ming dynasty ultimately fell, yet Changling remains a precious legacy left by the Yongle Emperor to posterity.

IV. Dingling: Unlocking the “Underground Treasury” of the Wanli Emperor

If Changling epitomises “grandiosity”, then Dingling stands as the symbol of “mystery and legend” – it is the only tomb among the Thirteen Tombs to have been excavated, and the sole site where we may enter an underground palace to witness imperial burial artefacts firsthand.

The occupant of Dingling is Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Yijun, arguably the most ‘peculiar’ emperor in Ming history: reigning for 48 years, the longest in Ming history, yet spending 28 of those years absent from court, indulging in feasting and revelry within the Forbidden City. But do not mistake him for ‘lazy’ — when it came to constructing his mausoleum, he was more dedicated than anyone. From the age of 21, he personally selected the site and finalised the design. Mobilising 30,000 craftsmen, the project took six years and consumed 8 million taels of silver – equivalent to two years' worth of the Ming treasury's revenue at the time. Adjusted for modern currency, that amounts to over 20 billion yuan!

We shall now descend these steep stone steps to explore Emperor Wanli's subterranean palace. Mind your footing, for these steps were deliberately preserved by archaeologists during excavation. Each tread carries the weight of history. The underground palace lies 27 metres below ground level—equivalent to a nine-storey building—maintaining a constant year-round temperature of approximately 15°C, some 10°C cooler than the surface.

The entire underground palace comprises three sections: the front hall, central hall, and rear hall, forming a long subterranean corridor. The front hall stands empty, devoid of furnishings, serving as the palace's ‘entrance hall’; the central hall houses the spirit seats of Emperor Wanli and his two consorts, alongside three enormous blue-and-white porcelain dragon vases. These once held lamp oil to fuel the ‘eternal lamps,’ though they were extinguished centuries ago; The most sacred space is the rear hall, the final resting place of Emperor Wanli and his two consorts. Centred within lie three colossal stone sarcophagi, known as the ‘coffins’: The largest, measuring 3.3 metres long and 1.5 metres wide, is Emperor Wanli's. Carved from a single block of white marble, its lid bears exquisite dragon motifs. The two smaller coffins beside it belong to Empress Xiaoduan and Empress Xiaojing respectively, their lids adorned with phoenix designs. The dragons and phoenixes facing each other symbolise the profound affection between emperor and empress.

Surrounding these sarcophagi, over 3,000 precious artefacts were unearthed during excavations, most of which are now housed in the Dingling Museum. Among these, the most renowned is Emperor Wanli's ‘Golden-threaded Winged Crown’. This golden crown stands 24 centimetres tall and weighs 150 grams, entirely woven from gold thread. Most astonishingly, not a single nail or drop of adhesive was used in its construction. Instead, 5,182 strands of gold thread, each as fine as a human hair, were meticulously woven together through techniques of ‘braiding, weaving, twisting, and layering’. At the crown's apex, two golden dragons wind with graceful curves, their scales distinctly visible. Each dragon holds a pearl in its jaws; the slightest movement causes the pearl to sway. This represents the pinnacle of ancient Chinese goldwork craftsmanship, a feat that would prove exceedingly difficult to replicate even today.

Regarding the underground palace, there is also the tale of the ‘door-blocking stone’. When archaeologists opened the palace gates, they discovered a 1.6-metre-long bluestone slab blocking the entrance, with a layer of small pebbles beneath it. It was later understood that this constituted an ancient ‘anti-theft device’: after craftsmen sealed the tomb's entrance, those inside would dislodge the pebbles, allowing the slab to slide down its grooved channel and bar the doorway. Even with the key, outsiders could not open it. Moreover, the tomb's walls were constructed using ‘glutinous rice mortar’ — a mixture of boiled glutinous rice paste blended with lime and loess. This mortar possesses greater strength than modern cement. Over centuries, the tomb walls have remained flawless, showing not a single crack and exhibiting minimal water seepage. One cannot help but marvel at the ingenuity of ancient craftsmen!

V. Cultural Insights: Deepening Your Understanding of the Thirteen Tombs

1. Feng Shui Culture: While we often refer to ‘feng shui’ today, it is not superstition but rather the ancient Chinese ‘environmental science’. The Ming Tombs' layout, with mountains encircling and waters winding around, embodies the principle of ‘harmonious coexistence between humanity and nature’ – mountains shield against winds, waters gather vital energy. Such an environment not only provided comfort but also aligned with the ancient pursuit of ‘unity between heaven and humanity’. From a modern perspective, this site selection philosophy is remarkably scientific: mountains block cold air currents, while water regulates the local climate, fostering exceptionally lush vegetation here.

2. The Symbolism of the Dragon: Within Chinese culture, the dragon is a divine beast reserved exclusively for emperors. The dragon motifs you observe at the Thirteen Tombs all depict five-clawed golden dragons, each rendered in distinct postures: some with heads held high and chests thrust out, others coiling through clouds, and still others clutching jewels in their mouths. These variations symbolise imperial power, majesty, and auspiciousness. However, in ancient times, commoners were forbidden from using dragon motifs. Even embroidering a dragon on clothing could incur punishment.

3. Ritualistic Norms: Every detail of the Thirteen Tombs adheres to strict ritualistic protocols. For instance, the stone statues lining the Sacred Way must number exactly 36 – six civil officials and six military generals – mirroring the Ming Dynasty's ‘Six Ministries and Nine High Officials’ administrative structure. Similarly, the pillars of the Ling'en Hall at the Changling Mausoleum were crafted from golden thread nanmu wood, while other tombs could only use pine or cypress wood. This exemplified the ‘hierarchical order’ – imperial tombs must be more magnificent than those of empresses or princes, with no deviation permitted.

VI. Visitor Tips

1. The site covers a vast area. Walking from the Sacred Way to Changling and then to Dingling involves approximately 3 kilometres. Comfortable trainers are recommended to avoid sprains.

2. The underground chamber of Dingling remains cool even in summer. A light jacket is advisable, particularly for the elderly and children.

3. Touching artefacts and photography are strictly prohibited within the exhibition areas. These relics, having endured centuries, are extremely fragile. We must all help preserve them.

4. Numerous cultural gift shops line the grounds, offering items such as miniature replicas of the Wanli Emperor's golden crown and dragon-patterned silk scarves. Should you wish to purchase souvenirs, please exercise caution in verifying authenticity.

Standing upon the Sacred Way, watching the setting sun stretch the shadows of the stone elephants, listening to the rustling of leaves in the breeze, one might almost hear the chiselling sounds of craftsmen six centuries past and glimpse the figure of Emperor Yongle on horseback making his rounds. The Ming Tombs are not merely a scenic spot; they are a frozen slice of history, a living legacy of culture. May today's visit leave you with lasting memories of this land embraced by mountains and waters, and of the tales preserved within these bricks and stones.